First invasive lionfish discovered in the southeastern Brazilian coast

Scientists call for urgent control measures to protect coral reefs from fast-moving, destructive invasion

A single fish caught with a hand spear off the Brazilian coast is making big waves for the entire southwestern

Atlantic. In May 2014, a group of recreational divers spotted an adult lionfish—the voracious invader Pterois

volitans—in the subtropical rocky reefs of southeastern Brazil (23oS; 42oW). A group of researchers, including

scientists from Brazil (UFF, UFSC) and USA (CalAcademy), used genetic analysis to link the lionfish to the infamous

Caribbean population of invaders. In light of a separate study detailing the lionfish penchant for eating critically

endangered Caribbean reef fish, news of lionfish in Brazilian waters raises alarm for Atlantic reefs and the region’s

already-threatened marine life. The discovery is published this week in PLOS ONE. Lionfishes are prolific breeders

made famous for threatening reef ecosystems outside their native Indo-Pacific distribution. Though the exact cause

of their initial Atlantic invasion is unknown, experts believe aquarium dumping in the mid-1990’s is at least partly to

blame. With flamboyant fins and vibrant, multi-colored stripes, P. volitans lionfish are popular additions to home

aquariums that occasionally end up in nearby waterways. Once free to breed in open waters, lionfish populations

can explode within a short timeframe. Some researchers estimate that one female lionfish can spawn more than

two million eggs per year. The researchers say the P. volitans individual found in Brazil probably reached those

water via natural long-distance larval dispersal. Case studies from the lionfish-ridden Caribbean hint at what is in

store for the southwestern Atlantic. Luiz Rocha (CalAcademy), along with a team of scientists from the Academy and

the Smithsonian Institution, recently zeroed in on Belize’s inner barrier reef to study the impact of invasive lionfish on

vulnerable Caribbean coral reef ecosystems. The stomach contents of area lionfish—analyzed in the Academy’s

Center for Comparative Genomics (CCG) — reveal just how quickly these invaders can devastate native reef

populations. The researchers concluded that many reef fishes share biological traits—including small size,

schooling, and hovering behavior—that make them a target for invasive lionfishes. The combination of lionfish

predation, limited range, and ongoing habitat destruction makes the social wrasse the most threatened coral reef

fish in the world. Brazilian reef fish with small ranges and analogous traits face similar risks in the face of new

lionfish invasions. Compared to the Caribbean invasion, a lionfish population explosion in Brazilian waters may

bring even more severe consequences. Brazilian reefs have relatively lower species diversity but a high number of

fish found nowhere else on Earth, many of which have small ranges. The country lacks any formal monitoring

programs aimed at early detection of invasive marine species, and is notorious for its struggles with fisheries

management. In December 2014, the Brazilian Minister of the Environment released new national “red lists”

identifying 3,286 species of plants and animals threatened with extinction—83 of which are aquatic animals

commercially exploited by fisheries. There are no bag or size limits for any species of fish, and commercial fishing

interests continue to hamstring efforts to enact new fisheries management plans. As regional ocean health

declines in the absence of regulations, fragile reef ecosystems are especially vulnerable to new threats.

Authors say that Brazilian fishes are being hit from all sides. Overfishing and habitat degradation are pervasive, and

not even the most basic fisheries data are being collected. The best—and easiest—way to control an invasion is by

trying to slow it down at the start. The recreational divers were the first to spot the P. volitans individual in Brazil, and

alert local authorities. It is important that Brazilian recreational divers keep their eyes out for lionfish and report

sightings immediately. However, there is another side of the story, which after decades of overfishing and lost of top

predators, even meso-predators, the arriving of the lion fish will simply fillup an ample vacant niche, with full of

preys. Only time and intense monitoring programs of the lion fish effects in a large geographic scale along the

Brazilian coast would unveiled the real effects.

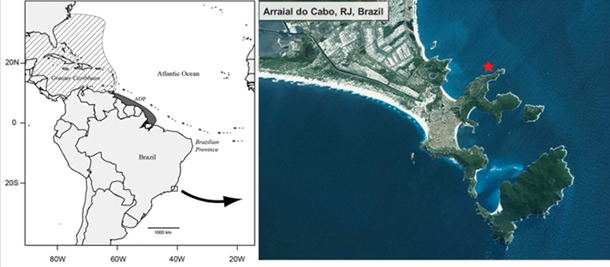

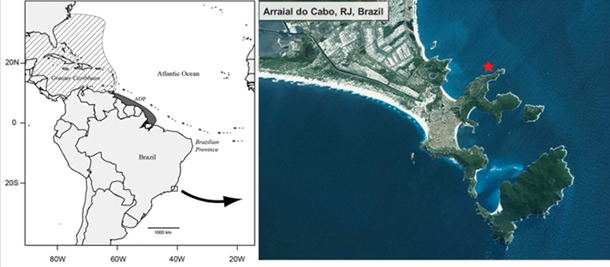

Fig1. Location (market with a red star) where the Lionfish was collected in Southeastern Brazil. Satellite image

by NOAA.

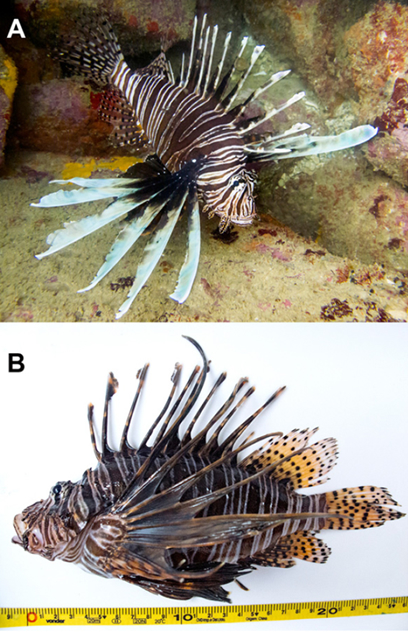

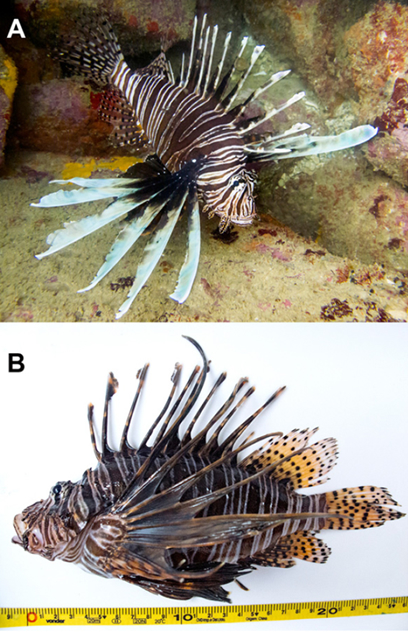

Fig 2. Underwater (A) and specimen phograph (B) of the Lionfish collected in Arraial do Cabo, SE Brazil.

Photos by MBL and MCB.

|